ECO SPEAKS CLE

ECO SPEAKS CLE is the podcast for the eco-curious in Northeast Ohio. In each episode, we speak with local sustainability leaders and invite listeners to connect, learn, and live with our community and planet in mind. Hear from the people and organizations that make our region a great place to live, work, and play.

ECO SPEAKS CLE is hosted by Diane Bickett and produced by Greg Rotuno.

ECO SPEAKS CLE

The Heat Will Kill You First: A Conversation with Author Jeff Goodell

In this episode of Eco Speaks CLE, we speak with New York Times bestselling author and climate journalist Jeff Goodell. Jeff has covered climate change for over two decades at Rolling Stone and is the author of seven books, including his latest book, The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death On A Scorched Planet. This is an engaging, thoughtful, and human book filled with stories that help us all understand how we can help address this moment.

What would you do if your casual seven-mile hike turned into a fatal encounter with extreme heat? That is one chilling tale we discuss as we dive into the dire realities of our rapidly warming world. Join us to understand the Goldilocks Zone, how heat is the driver behind many natural disasters, how our bodies react to heat, and the health risks we face even in cooler regions like Northeast Ohio. Stay with us and hear what it will take to address the drive change, the economic costs, legal actions against oil companies, the power of young voters, and how an encounter with a polar bear reminds us that we are all in this together.

Guest:

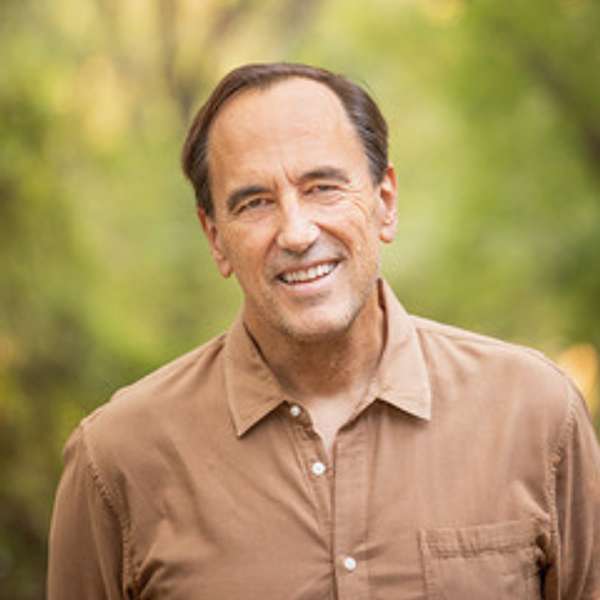

Author and Climate Journalist Jeff Goodell

The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death On A Scorched Planet

Follow us:

https://www.facebook.com/ecospeakscle

https://www.instagram.com/ecospeakscle

Contact us:

hello@ecospeakscle.com

You're listening to EcoSpeak CLE, where the EcoCurious explore the unique and thriving environmental community here in Northeast Ohio. My name is Diane Bicke and my producer is Greg Rotuno. Together we bring you inspiring stories from local sustainability leaders and invite you to connect, learn and live with our community and planet in mind. Hello, friends, we have a very special guest today from Austin, Texas, New York Times best selling author and climate journalist, Jeff Goodell. Jeff has covered climate change for more than two decades at Rolling Stone and other publications. You may have seen him talking about climate and energy issues on NPR and other major news networks and he is the author of seven books, including his new book the Heat Will Kill you First Life and Death on a Scorched Planet.

Speaker 1:I have listened to this book, I've read the book and recently had the privilege of hearing Jeff in person speak about his book at the Hudson Library. A few weeks ago I went with Greg, my husband, my daughter and we all agreed it would be really cool no pun intended to invite Jeff to join us on EcoSpeak CLE so we could also speak with you. So, as he was signing my book, I asked him and he said yes. First disclaimer I want to let you know that this book is not just another depressing book about climate change. Filled with charts and graphs. It is a little scary at times, but it is a thoughtful and human book. Jeff maintains that he is not a doomer and he is weirdly optimistic, but we all need to have our eyes wide open to address this moment. So welcome Jeff.

Speaker 2:Thank you for having me. Great to be here.

Speaker 1:So summer in Austin what was that like? I think you were traveling a bit for your book tour, but what did that feel like? You faced one of the hottest summers on record in Texas.

Speaker 2:Yeah, I mean you know many of us faced one of the hottest summers on record. I think it was the hottest summer globally on record, in sort of in human history and it felt to me like Austin was the center of it all. There was a strange feeling for two reasons. One is that I had spent three years writing about heat and thinking about heat, but then to be here and kind of experience it so relentlessly, it gave me new understanding of the sort of some of the subtleties of what it means to live in a place where it doesn't get below 100 degrees for like 50 days in a row. And also it was a strange feeling because I had written a book about heat. I was, the book was out, I was doing podcasts and interviews and talking to people like we're doing now. But it kind of felt like I was living in my own Stephen King novel because I had written this thing and then it kind of happened this past summer. So that was a sort of odd feeling.

Speaker 1:And so you were just stuck inside, the shades drawn and your air conditioning went out at one point, and you realized that you're really vulnerable to power outages, which we all are. So when did the title come to you? Just sort of in the middle of those days, or?

Speaker 2:No, the title came to me like a year ago Books are. One of the difficulties of doing a book like this is the need to be done more or less down a year in advance, and so you never know what the world's going to look like when your book comes out. And if you're writing a novel about 19th century romance or something, it doesn't matter. But if you're writing a contemporary contemporary events, whether it's politics or business or, in my case, climate change you never know what that world's going to look like when the book comes out. So that's always a little bit scary in the book writing business. The title came to me a year earlier when my publisher and I were going back and forth about what we should call this book and there was some debate about this title because it's very blunt, very scary in some levels, and there was certainly people at my publishing house who wanted it to be named something more less kind of threatening like heat or just something like that.

Speaker 2:But I really wanted it to be more confrontational, not because I wanted it to be more scary although that's OK, because I think we should be scared. As you said, I'm not a doomer, but I do think we need to be alarmed about what's happening in our world. But I also really wanted this book to be engaging in a personal way. I wanted it to be about you and your relationship with the weather and with the climate and with heat, and I think too much writing about climate change and too much talk about climate change is all about kind of future scenarios and future generations and people far away, and I really wanted it to have this feeling of this is happening to me and you now, and the book, or the title, I think, suggests that.

Speaker 1:And in your talk you talked how important it is for all of us to understand heat and the risks of heat, and that's one of the most important things we should be doing right now. You open your book with a story that kind of brings that message home how we're not we're all not immune from this. It's the story of the Garrish family, and would you mind telling us that story?

Speaker 2:Sure, and this is a story that I read in the media. It was the headlines when it was happening in the summer of 2021. And immediately intrigued me and I explored it more and came to sort of tell the story as fully as I could in the opening chapter of the book. And it's about the Garrish family who? Richard Garrish was 43 years old. His wife, ellen Chong, was 37. They had a one and a half year old child. He was a software engineer in Silicon Valley. She was doing various kinds of consulting and other business related things, and they got tired of living in the go-go world of Silicon Valley and moved to the Sierra Nevada foothills and they were starting a new life there, working remotely as many people did during the pandemic no-transcript.

Speaker 2:We really wanted to be closer to nature and more in tune with the sort of natural world around them, and one day they decided to go for a seven mile hike, and it was a July day. It was forecast to be about 104 degrees that day, which was hot. Of course, they thought of themselves as experienced hikers than they were. They, richard Garrish, had a conversation with his brother who was a kind of outward bound leader in Scotland who was very familiar with sort of outdoor risks and survival techniques and said to his brother it's going to be very hot tomorrow, you need to be careful, maybe you should reschedule. Richard said no, I understand, we're going to be fine, we're going to leave early, we have plenty of water. And they started out on the seven mile hike. They left early in the morning at seven o'clock and they had water with them. They had their dog with them. They had their one and a half year old daughter with them. Richard was carrying her in a backpack.

Speaker 2:They hiked about four miles down to the Merced River, which is a lovely river that runs out of Yosemite Valley there, and then they had to hike up about a three mile switchback, two and a half mile switchback of southern facing exposure, and it was around noon, so the heat of the day, unfortunately, when they started this hike and no one knows exactly what transpired.

Speaker 2:But that night their family and friends realized that they hadn't come home.

Speaker 2:They had people were making calls and they didn't hear from them and called the Sheriff's Department.

Speaker 2:Sheriff's Department sent out a search party and they found the entire family, including the dog and the daughter, dead on the trail about halfway up this steep switchback and at first they thought it was the Sheriff's Department, thought it was maybe a family suicide, or maybe they had drank something in the river that had some bacteria or something like that that had killed them, or they had stumbled over an abandoned mine that was that were carbon monoxide was leaking or something like that. But after a few weeks of investigation it became very clear that what happened is that they all died of heat stroke. And this is the story I tell in the opening chapter of the book, and it was really important to me to tell the story to really underscore this idea that we're all vulnerable, that even kind of youngish people in good shape, who you know on some level understand the risks of extreme heat, can still be killed and be killed very quickly, and in some ways it's the embodiment of the title of the book that we talked about a moment ago.

Speaker 1:The heat will kill you first. Yeah, so funny how our minds went. I think you know many of us will remember hearing that story reported on the news and our mind goes to everything but the heat. You know we think there was foul play or whatever involved In your book. I thought it was really important because you talk about the Goldilocks zone and it helps us understand how fragile and what a fragile place we all are. Would you mind talking about that?

Speaker 2:Yeah, the Goldilocks zone is a really important idea that I borrowed from planetary scientists who look for life on other planets.

Speaker 2:You know, when they're looking for life on other planets, the best indicator they believe for that is the presence of liquid water.

Speaker 2:And so they look for planets that, if it's too cold, of course, the liquid water is ice and you have, you know, balls of ice, like Pluto or something like that.

Speaker 2:Or if it's too hot, you have places where the water is all vaporized and there's no presence of water, like, say, venus, when they're looking for, so they're looking for the presence of liquid water, and that is, they believe, the temperature zone in which life can exist. And I borrowed this term from my book because it's really important to grasp when you think about the risk of heat, this notion that we humans, and basically all of life that we recognize around us, has evolved in a certain sort of zone of heat and we are really good at dealing with heat within this certain range that we've evolved in. But as our planet heats up and as these extreme events get more and more extreme, we're moving out of that Goldilocks zone. And as we move out of this Goldilocks zone, our bodies have a much more difficult time dealing with it. The risks, not just to us but to all living things, increase exponentially, and it's a really important concept to grasp when we think about not just the risk of extreme heat but the dangers of climate change in general.

Speaker 1:So when we talk about the Goldilocks zone, I thought that part of the book was helpful in helping talk to other people about climate change being able to say you know, we've all evolved within this certain range and evolution doesn't happen fast. We can't quickly adapt to being out of that zone. Many things in your book helped me kind of think through my conversations with people and how to best address climate deniers and such, and I think helping explain how things will happen to someone individually gets people's attention. Can you talk a minute about how heat does kill? I read that more people die from heat stroke right now already than any other natural disaster and it's an equal opportunity killer. What happens when a body goes through heat stroke? You started to feel some of those effects yourself when you were hiking, I think, in Nicaragua. Can you explain what that felt like?

Speaker 2:Yeah, so like 10 years ago so long before I began this book and what happened? To be on vacation in Nicaragua and went for a hike up a volcano conditions not so different than what actually killed the Garrosh family, one of the reasons I was so drawn to that story I started to hike up a steep volcano and I had what I thought was plenty of water with me and I was with some other people and we started hiking and I started sweating and I started getting a little dizzy, but I didn't really think anything about it. It wasn't that hot, it was maybe 85 degrees, but it was very humid. So that changed the dynamic somewhat, but I started to get dizzy. I started to feel in my heart really pounding in my chest and at a certain point my body just started to sweat it's not enough to say I was sweating Just like water started pouring out of my body. It was just this strange, surreal feeling of my, and I know now that my body was desperately trying to cool off and I started to get a little bit hallucinogenic and losing my balance, and the people I was with fortunately recognized what was happening to me and insisted that we stop and I just sit there and cool down until I regained my body temperature, lowered a little bit, and it took about an hour and a half of rest in a shady spot for myself to come back, my body temperature to get back to normal, and it was very frightening, but I didn't really, and I understood then that it was about heat. But I didn't. That was not the genesis of the book at all. But when I started writing about heat then for this book, I reflected back on that and I realized that I was experiencing the beginnings of heat stroke.

Speaker 2:And so what happens when we're exposed to extreme heat for any period, whether it's because you're locked in a hot car, or whether it's because you're on a high kind of volcano and Nicaragua, or whether you're working on a rooftop In Ohio on a really hot day, you know the we, our bodies, have one mechanism to cool off, and that is sweat. And that's how we do it. And what happens is our body temperature begins to rise. Is you know, these sweat glands spray water onto our skin and as that water evaporates by evapotranspiration, it carries the heat away. And so, in order to help make this more efficient, our heart starts pounding and pushing our blood out Towards our skin to be at this sort of cooling perimeter, and so one of the initial things that you feel when you are exposed to extreme heat is your heart starts pounding harder and harder and faster and faster and it pulls blood away from your brain and some of your internal organs in order to get it out around your skin, which is one of the reasons you feel lightheaded and, in some cases, even hallucinogenic, because the brain, the blood, is actually being pulled away from your brain, and this is one of the reasons why people who have any kind of heart or circulatory problems are much higher risk.

Speaker 2:Of heat exposure Is because it puts so much strain on your heart, because basically, that's the only mechanism our bodies have, and so, as it gets hotter and hotter, our heart starts pounding faster and faster and faster, trying desperately to get as much blood as possible out to the periphery of our body, so where it can be cooled off.

Speaker 2:And if it works, as it did in the case with me and Nicaragua, I was able to get into the shade, stop exercising and generating my heat. My body was able to get regain control. But if it, if it can't regain control, either because you continue exercising and ignoring this, or because the heat is so extreme that you can't get out of it, then you get into real serious trouble. You know heart failure. But then at a certain point, around 105 degrees body temperature which is not really that you know, it's only six degrees or so from a normal body temperature Really terrible things start happening, like you know. The membranes of your cells begin to melt or denature as it gets hotter and hotter and your body literally begins to sort of melt from the inside and you start hemorrhaging inside and all kinds of terrible things happen and death inevitably follows.

Speaker 1:Yikes, that's, that's pretty scary, it's, it's it's.

Speaker 2:It's a really you know writing about the details of extreme heat and what it does to your body. It does feel for me as a writer, kind of just horrific going into the details of it.

Speaker 1:Yeah, well, you know, here in Cleveland we're not accustomed to heat. We had just two days over 90 degrees on, like Texas and the rest of the world. Yet you know, I think there's a feeling here that you know we think we're going to be okay in the midst of climate change, that you know we live here with our great lake and our cooler climate and that'll make us safe from, you know, some of the worst effects of climate change. Yet heat is. You know, we still had a month long drought in May. We still had tornadoes and torrential rains come through in August. But some will just say it's just the weather, you know. And how is that thinking wrong?

Speaker 2:That thing is wrong because you know yes, it's true, of course that the weather has always been changing. I mean, that's obviously true, and there's been times in the past on Earth, in Earth history, when there were alligators in the Arctic. You know where the Arctic is, now palm trees growing where Antarctica is. I mean, there's no question that there's been extreme changes in the Earth's climate over time, but those climate changes have all been driven by natural processes, mostly volcanic reactions, that have belched CO2 into the atmosphere and change the temperatures of the Earth's climate. What's happening now is very different. We are belching CO2 into the atmosphere ourselves by burning fossil fuels and by loading up the atmosphere with fossil fuels very quickly, much faster than volcanoes did in times in the past. We are changing the climate much more quickly than it's ever changed before, and that would be fine, except for the fact that, as we talked about earlier, we have all evolved to deal with a certain range of temperatures, and so we are pushing our climate system to move much more quickly than it ever has in the past. And we meaning humans and other living forms and also, by the way, everything that we've built, like railroad tracks, bridges, all kinds of things even your iPhone will give you an alert when it's too hot are not adapted to these radical changes.

Speaker 2:And it's true that Ohio is actually there are certainly better and worse places in the world than I'm talking to you from one of the worst places. I'm in the belly of the beast. The belly of the beast, as you said. Yeah, totally, here in Texas we're dealing with droughts, we're dealing with extreme heat. We have a whole coastline on the Gulf that is extremely at risk of sea level rise. We have lots of problems migration problems, crop failures here that make us really vulnerable. But when people ask me three or four years ago, where should I move, everybody wants to know where they should move to get to reduce the risk. One of the places, first of all, I would say that there's nowhere that you can go that you're going to be protected from the risks of climate change. I mean, just look at the wildfires in Canada and the sort of northern boreal forests where, up until recently, a lot of people thought that was a very cool place to be.

Speaker 1:Yeah, and then those all caught fire this summer.

Speaker 2:Yeah, and look at what happened in the Pacific Northwest in 2021. I mean, you mentioned in Ohio you've had a couple of hot days and it's a relatively mild summer climate. So too was the Pacific Northwest. Nobody thought that British Columbia, for example, could have days when they had 121 degrees, and we had towns in British Columbia that got so hot they more or less spontaneously combusted and burned to the ground. Portland 115, 116 degree days. We had 1,000 deaths over a four-day period in the Pacific Northwest.

Speaker 1:Yeah, those were crazy stories you tell about Paris and Seattle area and Chicago even. I think we just didn't really hear a lot about that on the news other than just quick little reference.

Speaker 2:But there were a lot of people that died.

Speaker 2:Yeah, so no one's immune to it. You can make the argument, as some people do, that here I am in Texas and it's really hot. It's been really hot all summer. But a lot of people in Texas say, well, we're prepared for it and we know how to deal with heat, and to some degree that's true. Obviously it's been hot in Texas for a long time.

Speaker 2:But we're getting to these extreme levels where people are not prepared for it and people who are outside the bubble of air conditioning or even taking short walks and things like that are really at risk. In Ohio there is not this sort of heat awareness that there is in Texas, and that increases the risk because people don't understand what the signs of heat exhaustion, heat stroke, when hot weather comes, what to do, how to handle it. It's the inverse of what happens here in Texas. When I first moved here four years ago, we had an ice storm that lasted four or five days and I had come from upstate New York, where I drove an ice storm all the time and really knew what to do with ice storms. When we had an ice storm here in Texas, people freaked out.

Speaker 2:They had no idea what to do. Their cars were crashing all over the place, water tanks were bursting. I mean, people had no idea how to handle it. And similarly, in places that are not used to heat, when it comes it's, in a way, exponentially more dangerous because people don't understand how to deal with the risks.

Speaker 1:Well, yeah, we make fun of people here because they can't drive in the snow, but we're equally dumb about heat. So I'm sure that's part of a lot of the climate planning that's happening here in Northeast Ohio with our climate action plans and such. But heat is a driver for, as you maintain, droughts behind Dengue appearing in Florida, rise of malaria because animals are on the move and plants. So it's kind of a stark picture. But I'd like you to talk a little bit about besides heat. Heat is going to drive change and it could be an engine for positive change. It will have to be. What else will accelerate change? Are there lawsuits against oil companies? Is just going to drive change? The economic cost of all these natural disasters going to help drive change? Young voters, will they drive change? What's your take on all that?

Speaker 2:I think all those things are driving change. I think that there's no one single thing. I think that people are gradually becoming more and more aware of the reality of what's happening. I think that extreme events like these summers the summer we've just been having, where we had the hottest summer globally on record, and we had all of these extreme heat events all over the world we're making it very, very clear that this is not some sort of invention of liberal tree huggers, but this is an actual, physical fact of what's happening to our world. I think that's driving change.

Speaker 2:I think the economics are really important. Here in Texas, the fossil fuel capital of the country, we also are the leaders in wind and solar energy, because there's a lot of money to be made in wind and solar right now, because fossil fuels are becoming more and more expensive. By far the cheapest way to generate electricity virtually everywhere in the world now is through renewable power. That is dominating the growth in green jobs related to all kinds of clean energy, from new kinds of rewiring of the grid to electric vehicles, to all kinds of progressive thinking about how to deal with and adapt to these changes. That is where the economic growth is going. The economic growth is not going. No one's building more coal plants. We're not going to build more coal plants. If your economic model is built around building more coal plants, you're going to be in trouble.

Speaker 2:It's this inevitability of this energy shift. Just as we shifted from whale oil to petroleum, this shift away from fossil fuels to clean energy is happening. That's a huge driver, I think, politically, you have a younger generation that understands all of this. The lawsuit in Montana where you had 12 young people suing the state of Montana for an article in their constitution that required a habitable climate, basically a habitable environment One of the decisions from the judge to bring it to trial is really important. We're going to see more and more of this drive for accountability from younger people, from others who have been injured and harmed by these climate impacts. I think that's going to drive a lot of change too.

Speaker 1:I wish that story had gotten more pressed than it did, at least from here. There was something else happening in the news that day. I can't remember, but that court case didn't get a lot of press here. What would you say to the hangers on who just want to still hang on to fossil fuels out of either ignorance or greed or political persuasion? What would you say to them? How do we talk to those people to get them out of their echo chamber? Is there a way? What would you say to those people you've heard about?

Speaker 2:It's really hard because, as I've learned, living here in Texas, the fossil fuel capital of the world, where I spend a lot of time when I live in the northeast I didn't spend that much time actually with people who are culturally and economically deeply invested in the fossil fuel world, but here in Texas I do and I don't. First of all, I don't think that there's any kind of magic words that we can say that's going to change Everybody. I think that everyone has their own reasons. Sometimes it's political, sometimes it's economic. They're invested, you know they have a, you know they've invested their retirement in, largely in, you know, exxonmobil, say, and they want the dividends and they want the money and they don't want to see that kind of being taken away.

Speaker 2:You know, unfortunately, a lot of debate about the transition to clean energy and climate change has become enmeshed in the culture wars that we're seeing in America. Right that, you know it's. There's been a strong push to kind of debase the legitimacy of science in America. Recently we see that in the anti-vax movement, the rise of the anti-vax movement, which has, you know, really tried to cut the ground out from underneath a lot of the best scientists and the best kind of scientific thinking about what to do, about how to deal with COVID. That's a you know, that's a troubling sign when you think about extending that to the climate movement. You know, and I also think that there's a certain percentage of the population that will never be convinced that this is urgent real and that this is the best thing to do.

Speaker 1:You need to move on without them, right?

Speaker 2:Right, and so that's okay.

Speaker 1:Yeah. You know, Well, I know we're running short of time, so I know you've traveled literally to the ends of the earth to write this book. You've been to Antarctica. There's a great chapter about your trip to Antarctica. You end with your trip to the Canadian Arctic and an encounter with a polar bear, and I would wonder if you could just close by telling that story a little bit and what she taught you. What did not being eaten by a polar bear teach you briefly?

Speaker 2:Yeah, that's not something that I ever thought that I would have to think about, about what not being eaten by a polar bear would teach me, but in fact I did. It is the last chapter of the book and readers can read the full story. But a few years ago not because I was trying to do research particularly on this book, I was doing other kinds of research I went to Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic, which is kind of across the Greenland Sea from Greenland and it has one of the highest population of polar bears in the world and we knew that we were going to be seeing a lot of bears. We took a 350-mile cross-country ski trip across Baffin Island, me and two other scientists, and we basically pulled 100-pound sled each of us behind us. We were on skis the entire time. We didn't see another human being for seven weeks. We saw a lot of polar bears and we were out there and we realized how vulnerable we really were.

Speaker 2:A lot of people who do these kinds of trips in these places bring dogs, because the dogs are very good at barking when a bear comes near, which is particularly important at night when you're sleeping out on the ice and you're laying out there like hot dogs on the ice, and one of the things that makes polar bears so scary is that they're the only bear that is actually predatory, that will actually track you down and hunt you. Grisly bears won't do that. Grisly bears are dangerous, but they're dangerous if you are on a hiking trail and come around a corner and surprise them, or you come across them with their cubs or something, but they won't actually hunt you down. Polar bears will hunt you down and we got out there and about halfway into our trip we realized there were a lot of bears around us and a lot of these bears were hungry because the sea ice that they used to hunt seals had melted particularly much that year and they were not able to get as much food as they wanted, so they were looking for fresh meat. Basically, and it was a very, very alarming experience to be out in the middle of the ice on Babban Island and realize that we would wake up in the morning and see these big bear prints of 10 or 15 feet from our tent and realize how vulnerable we were.

Speaker 2:But we finally made it through all of this and we got to our last campsite where we had used a satellite phone to call some Inuits to come with some of the bills to get us over this one ridge back to a village where we could get a small plane to fly out. And we had rendezvous there. And we got there. We were exhausted, we were out of food and we realized it was sort of a seal slaughterhouse zone. There was blood all over the ice, there was seal parts of seals everywhere, polar bear tracks everywhere, and this was where we were supposed to rendezvous with the Inuits and we were too tired and too exhausted to move on from that point. So we basically skied a couple hundred yards away from this area and camped.

Speaker 2:It was a very terrifying night, knowing that there were bears all around us, but we survived. Obviously we woke up that night. That morning it was a blue sky and then Inuits were supposed to come at around noon to pick us up At about 10 o'clock. We went back into our tent in 10 o'clock in the morning, after wandering around outside for a while, to have a final ceremonial kind of cup of tea around our little camp stove. We had a cup of tea and while we were having the cup of tea there, whenever we camp we would put what we call a bear wire up around the tent, which is like just a little thin piece of copper wire that was connected to a battery. If that piece of copper wire broke, we knew something was approaching the tent. A little tiny alarm would go off and we would have 30 second alert to whatever was coming.

Speaker 2:But anyway, we were sitting there having our tea and the alarm went off and I thought it was just wind, because often the wind would knock the bear wire down and it would break and the alarm would go off. We had just been out there a few minutes ago. I hadn't seen anything.

Speaker 2:I unzipped the tent, stood up to get out and see what was going on and there was a female polar bear charging the tent right when I ended up there and I stood up and she stopped and she was like literally 15, 10, 15 feet from the tent, fully intent on coming in and getting us, and she stopped and was as surprised to see me as I was to see her and she stood up on her back legs and we had this sort of eye to eye contact for, you know, it seemed like five minutes, but it was actually probably 30 seconds where, you know, she looked at me and had to make a decision about whether she was going to eat me or not and she easily could have. I was standing right there and she had two cubs with her at her feet and clearly very hungry, but for whatever reasons, she made some grunting sounds and dropped down and essentially walked away. And for me it was such a powerful moment because not only because, of course, she decided not to eat me, but I really realized how much we're all in this together. You know that she was trying to survive.

Speaker 2:The climate change was impacting her life in a very powerful way. She had cubs to feed. She couldn't get the you know the seals that she needed for her meals, so she was exploring other options and for me it really underscored that this is not just about what's happening to you and me, or to people in Ohio versus people in Texas, where I live, or in India or China. It's about everything that's alive on this planet and that, as we continue to burn fossil fuels and heat things up and change things, we're putting everything kind of at risk, and we're doing this and we're all in this together, and that, to me, was somehow profoundly disturbing and also, though, profoundly hopeful and moving.

Speaker 1:Yeah, well, I think she wanted you to write this book, so that's why she didn't eat you. So I'm glad you're safe and I very much appreciate you writing this book. You will have a few hundred more book sales, I think, because of this podcast. So thank you so much for your time and keep up the good fight.

Speaker 2:Great, thank you. Thank you so much for having me. It's a pleasure.

Speaker 3:We hope you've enjoyed this episode of EcoSpeak CLE. You can find our full catalog of episodes on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. New episodes are available the first and third Tuesday of each month. Please follow EcoSpeak CLE on Facebook and Instagram and become part of the conversation. If you would like to send us feedback and suggestions, or if you'd like to become a sponsor of EcoSpeak CLE, you can email us at hello at ecospeaksclecom. Stay tuned for more important and inspiring stories to come.

.png)